04 — Procurement

NOTE: This module requires collaboration with the school administration to include those responsible for purchasing.

4.1 WASTE MANAGEMENT – HOW IS IT DONE TODAY?

An important part of the Plastic Free Campus program is understanding the practicality of different potential solutions. Start with a basic understanding of the local waste management capacity. From there this might show how changes to procurement can have a significant influence on waste management and potentially save costs.

Assignment: Complete 4A Waste Management Survey

4.2 WASTE MANAGEMENT – HOW TO IMPROVE IT?

As stated before, recycling is a complicated and sometimes imperfect process of converting waste materials into new materials which ideally promotes the reduction of raw materials and limits energy use and pollution. But it has often been falsely heralded as the solution to plastic pollution. It is not that simple. Recycling is a hugely energy-intensive process and can still be very polluting.

It takes 75% less energy to make a plastic bottle from recycled plastic compared with using ‘virgin’ materials. Using a tonne of recycled plastic bottles (recycled PET or recycled HDPE) in new bottles saves around a tonne of CO2eq. Statistics from WRAP

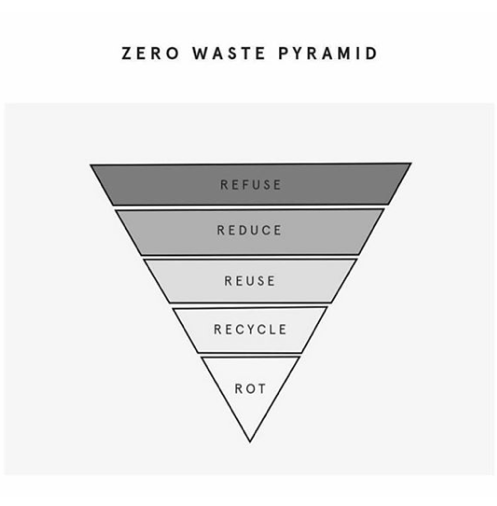

Therefore, your efforts should be focused on first refusing and then reducing and reusing or even repurposing plastic, and then recycling.

At many schools, a lack of understanding about why and how we separate waste can create cross-contamination of bins on campus.

If general unrecyclable waste gets mixed in with recyclable waste, it usually means (depending on the waste provider) that all the recyclables are contaminated, and will all be classified as general waste. Therefore, it is important to only throw recyclables in the recycling bin to ensure everything gets recycled.

Here are some ideas to encourage better recycling practices on campus:

- Location of the bins on campus: make sure these are in areas of high “foot traffic” or near vending points.

- Better labelling on bins: ensure that it is absolutely clear what goes into each bin. This can be done with photos of commonly consumed items as well as items sold directly on campus.

- Bin Busters (either members of the EcoCrew or volunteers) can direct the flow of waste regularly to explain to people where waste goes and why.

- Regular bin audits to track the effectiveness of recycling and to identify areas high in contamination. These can also help with getting key data to communicate to the school community, e.g. “1 out of every 3 recycling bins was cross-contaminated with general waste”.

4.3 PROCUREMENT – HOW TO IMPROVE IT

The list of items to focus on in procurement should be driven by results from the waste audit you completed in the Module 1. These examples should give you an idea of potential sustainable swaps, but this has to be driven by your local context, waste capacity and budget. In some cases, a 1-to-1 swap may not be the best solution. Can you think of how you can revamp or re-engineer a process to minimize the use of resources?

It’s important as well to remember that going “plastic-free” or “low waste” does not happen overnight. Indeed, it may be a shock to the school’s system to change procurement too drastically. That’s why we encourage reviewing the results of your audit and identifying what are the simplest procurement changes that can be implemented, all while communicating these changes to your community. You do not need to change everything to make a huge difference in your plastic footprint, and your school may still benefit from some economies on procurement!

Also, there is no “one size fits all” solution. As mentioned above, waste solutions must be local because of the different types waste management capacity in each area. While it may work for one school to switch from single-use plastic to compostable cutlery, another school’s local waste management may not have the industrial composting facility necessary to process such materials, so this swap would not make sense.

Top tip: Remember the waste hierarchy – go for refuse first, then reusable and if that isn’t feasible then find alternative (non-plastic) single-use materials.

| Item | Plastic Free Campus alternatives | Notes |

| Single-use water bottles |

|

Requires drinking water available throughout the school. |

| SUP bottles for other drinks |

|

Requires vendors willing to sell wholesale or time to make fresh juice |

| Single-use cups for drinking in the cafeteria (daily basis) |

|

Requires in-house dishwashing capacity |

| Single-use cups for events |

|

See Module 5 Events for further strategy |

| Plastic wrap for sandwiches |

|

Requires covers for the sandwiches |

| Condiments |

|

|

| Shrink wrap for fresh-baked pastries |

|

|

| Yoghurt containers |

|

Requires vendors who will sell yoghurt wholesale |

| Cups for hot drinks |

|

|

| Coffee/tea pods or bags |

|

|

| Plastic stirrers |

|

|

| Plastic cutlery |

|

Requires an upfront initial investment but will pay off after a few months of use. |

| Plastic dishes |

|

Requires an upfront initial investment but will pay off after a few months of use. |

4.4 PROCUREMENT – THE BUSINESS CASE

It is important to make these changes financially feasible for your school. While each school is different, we recommend you identify all the potential costs (spending) and savings over a year to justify your purchases. Don’t forget to bring in the goodwill that is generated by a community proud of doing something good.

It is also important to note that gathering strong data in the earlier modules will help you to demonstrate the impact and provide a strong base to be able to later apply for external funding for larger-scale procurement changes, like installing more water fountains around campus.

We suggest the following guidelines for procurement changes:

- Working with technical services to re-think processes rather than doing 1-to-1 replacements, as “compostable” packaging is often

- not compostable and

- more expensive

- Order in a co-op with other schools to take advantage of volume discounts

- Identify the breakeven costs of single use versus reusable items

Cost of reusable (each) / Cost of disposable item (each) = breakeven point (uses)

Example: Reusable cup = $1.00 each / Disposable cup ($0.05 each) = 20 uses

Therefore, after 20 uses of that reusable cup you are saving money!

For a more detailed approach to analyse costs and benefits of reusable products, including implementation costs (labour, washing infrastructure) and payback period, follow this link:

4.5 COMMUNICATION

Use data to tell the story: calculate how much was being spent on solid waste hauling at the beginning of the year and calculate how changes such as students coming to school with plastic-free lunches or if changes to procurement have reduced plastic waste.

Use this data to explain to the school community what has changed and what this means. For example, if water refill stations have been installed and plastic water bottles removed

Let students know to bring their own water bottles to school.

4.6 MEASURING IMPACT AND LESSONS LEARNED

This module can result in a lot of positive change. It will be important to measure the impacts to demonstrate the value of participating in the PFC programme to school leadership and the rest of the school community.

- What changes to procurement have been made?

- What items will no longer be purchased by the school?

- Is there a cost savings from this?

- Is there a cost for any replacement, such as washing reusable items?

- Is there a reduction in waste generated from elimination of these items?

- Is there a cost savings from reduced waste generated?

- Measure waste generation at intervals through bin audits, to demonstrate decreased general waste generation by weight

- Measure recyclable waste generation at intervals through audits of recycling bins, to demonstrate decreased plastic recycling by weight.

Discuss as a group how the negotiation process went.

- What could have been done better?

- Which negotiating tips from 4.1 worked well?

- Which negotiating tips from 4.1 did not work as expected?